Lake Huron’s Frozen Secret: The 42 Children Lost Beneath the Ice

Lake Huron’s Frozen Secret: The 42 Children Lost Beneath the Ice

A Silence That Lasted Nearly Half a Century

The ice of Lake Huron has always been treacherous, capable of swallowing ships and silencing storms. But for the families of the Red Pines Reservation, it swallowed something far more precious—their children.

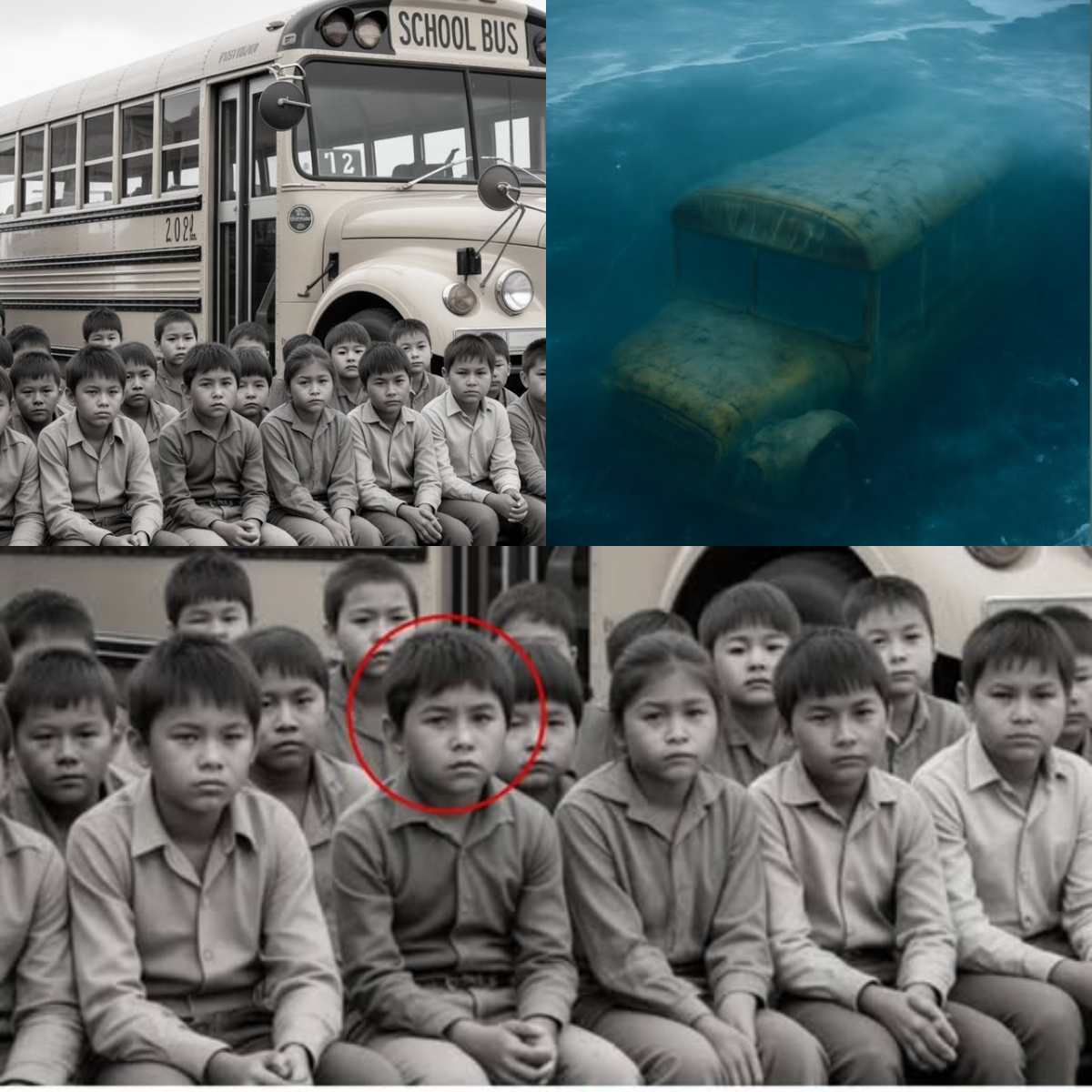

On a crisp spring morning in 1948, a yellow school bus carrying 42 Native American children set out from the reservation toward the nearby town. It never arrived. No search planes combed the skies. No national alerts were sounded. The families, silenced by grief and marginalized by a country that barely acknowledged their existence, were told a simple story: “It was a tragic accident.”

But there were no funerals, no bodies, no closure. Just an oppressive silence that stretched across generations.

The Day the Silence Broke

Nearly half a century later, in 1995, a sonar crew conducting a routine underwater survey for commercial shipping lanes stumbled upon an anomaly. At first, they thought it was debris from a wreck. But as the sonar image sharpened, outlines appeared: a rectangular shape with rounded edges, unmistakable to anyone who had ever ridden to school.

A bus.

When divers descended into the cold depths, their lights illuminated the impossible: a perfectly preserved school bus, windows intact, its paint dulled but still visible beneath the algae. And inside, skeletal remains. Row after row, seat after seat. Tiny shoes, rusted lunchboxes, a small doll still clasped in bone-thin fingers.

Lake Huron had not erased their story—it had kept it frozen in time.

A Story Buried, Then Resurrected

News of the discovery made local headlines, but the national media barely touched it. A few brief wire stories labeled it an “unfortunate accident,” echoing the same official explanation given in 1948.

But for one journalist, that wasn’t enough.

Michael Gray, then a young reporter for a Detroit weekly, had grown up hearing whispers about “the bus that never came back.” His grandmother, a teacher on the reservation, had always insisted something darker had happened.

“When I saw the headline in ’95, I knew this was it,” Gray recalls. “I dropped everything. Because you don’t just lose 42 children, and no one asks questions.”

The Official Story—And Its Cracks

In 1948, local authorities claimed the bus had slid off a bridge into the lake after icy conditions. They told families that the children had drowned instantly, and that recovery was impossible due to “dangerous waters.”

But Gray’s research uncovered troubling inconsistencies:

-

Weather reports from that day showed no ice and clear conditions.

-

Bridge records revealed no structural damage consistent with a bus crashing through.

-

Police archives contained no official accident reports.

“It was as if the tragedy had been written in pencil, easy to erase, easy to rewrite,” Gray said.

Families Left in the Dark

For decades, the families of the Red Pines Reservation lived with unanswered questions. Some were told their children had been taken to “special schools” and would be “better off.” Others were pressured into silence, threatened with loss of their land leases if they “caused trouble.”

Elder Martha Running Deer, now 89, still remembers the day her younger brother boarded that bus.

“My mother cried every night for years,” she told reporters in a trembling voice. “They told us it was an accident. But in our hearts, we knew it wasn’t. We knew someone had taken them from us.”

A Pattern of Disappearance

Gray’s investigation soon connected the tragedy to a broader, more sinister history: the forced removal of Native American children during the mid-20th century. Across the United States and Canada, Indigenous children were taken from their families and placed in residential schools, where many faced abuse, neglect, and forced assimilation.

What if the Red Pines children had been destined for such a school—but something went horribly wrong?

Gray uncovered declassified documents from the Bureau of Indian Affairs suggesting “transportation initiatives” were underway in the late 1940s. One chilling memo referred to “relocation units” designed to “reintegrate” Native children into society.

“Call it relocation, call it assimilation,” Gray said. “But when 42 kids vanish and reappear in a bus at the bottom of a lake—this is not an accident. This is a cover-up.”

The Conspiracy Unveiled

Further digging revealed that the bus route the children were supposed to take in 1948 had been changed at the last minute. No one could explain why. Records of the driver’s identity were missing. The bus itself, once pulled from the lake, was found to have locked doors from the outside.

“They didn’t drown by chance,” Gray said bluntly. “They were sealed in.”

The implication was horrifying: the bus had been deliberately driven into the lake, turning it into a tomb. Whether it was to silence witnesses, prevent escape, or erase a failed relocation scheme, the result was the same—mass death, buried under silence.

The Weight of Truth

By the early 2000s, Gray had published his findings in a series of articles that rocked the local community. The federal government denied involvement. State officials called it “unsubstantiated speculation.”

But for the families, the evidence was enough. They gathered at Lake Huron’s edge, holding a memorial for the children whose names had never been carved into headstones. They prayed, sang, and finally spoke aloud the grief that had been silenced for generations.

“We carried this pain like a ghost,” Martha Running Deer said. “Now we can set them free.”

The Journalist’s Lifelong Quest

Gray’s work came at a cost. He faced lawsuits, professional blacklisting, and threats. But he refused to stop.

“People told me to let it go,” he admitted. “But how do you let go of 42 children? How do you let go of a truth that was buried with them?”

He later wrote a book, Frozen Silence: The Lake Huron Tragedy, which detailed the conspiracy and sparked international attention. Indigenous rights groups demanded recognition of the event as part of the broader history of systemic abuse.

Lake Huron Today: A Haunted Place

Today, the site of the discovery remains a place of mourning. Divers occasionally leave offerings—feathers, flowers, small toys—at the bus, which still rests on the lakebed, preserved by the cold.

The Red Pines Reservation holds an annual ceremony, reading aloud the names of the 42 children so they will never again be silenced.

For tourists, Lake Huron remains a scenic wonder. But for those who know its story, its waters hold not just beauty, but grief.

Unanswered Questions

Even now, mysteries linger. Who ordered the relocation? Who locked the bus doors? Why was the tragedy erased from official records?

The government has never acknowledged wrongdoing. No official apology has been issued. For the families, closure remains incomplete.

“Justice may never come,” Gray concedes. “But truth—that’s what we have. And sometimes, truth is the only justice history will give us.”

Conclusion: The Weight of Memory

The story of the Lake Huron bus is more than a local tragedy. It is a window into a broader history of Indigenous suffering hidden beneath America’s surface. For 47 years, silence ruled. Then a sonar ping broke that silence, forcing a reckoning.

The children of Red Pines may never have their day in court. But they have their story back. And as long as it is told, their memory endures.

As Martha Running Deer whispered at the most recent memorial, standing by the icy shore: